Mies’ Medium

April, 2020

CARTHA Journal

CARTHA Journal

There are many surreptitious narratives about the infamous court-house (Patio-House or Hofhaus) credited to Mies van der Rohe from 1931-38. The name court-house is a mystery, the nature of authorship seems to be tied to a dialogue between student/teacher rather than from Mies’ practice, and the lack of a real construction or execution of any real examples leads many towards imagination.

The surreptitious narrative that is most intriguing however, is the story of how the house has transcended from a Bauhaus and IIT student assignment to become a sort of proving ground for other architects at the beginning of their career. In this test, the court-house serves as the template for their first house, by reconstructing the original brief they adapt it to their own interrogations into the hardcore of architecture. You can see traces of the house in many young architect’s work, but for this argument we will focus on versions that adapted the brief to present new paradigms for the court-house project. It’s important to study these inaugural projects because in their inadequacy and inexactitude, they often reveal early ideas hypothesized and tested, and are the preliminary trials of full-fledged architectural ideas we’ll see executed later. A note on the name: the court-house project has gone by many names, patio house or patio villa being the colloquial name in europe and canonically formalized as a the court-houses in Philip Johnson’s 1947 Moma exhibition.

The surreptitious narrative that is most intriguing however, is the story of how the house has transcended from a Bauhaus and IIT student assignment to become a sort of proving ground for other architects at the beginning of their career. In this test, the court-house serves as the template for their first house, by reconstructing the original brief they adapt it to their own interrogations into the hardcore of architecture. You can see traces of the house in many young architect’s work, but for this argument we will focus on versions that adapted the brief to present new paradigms for the court-house project. It’s important to study these inaugural projects because in their inadequacy and inexactitude, they often reveal early ideas hypothesized and tested, and are the preliminary trials of full-fledged architectural ideas we’ll see executed later. A note on the name: the court-house project has gone by many names, patio house or patio villa being the colloquial name in europe and canonically formalized as a the court-houses in Philip Johnson’s 1947 Moma exhibition.

Court-houses, 1931-1938

Mies van der Rohe

Thesis House, 1942

Philip Johnson

Patio Villa, 1984-88

OMA, Rem Koolhaas

Weekend House, 1997

Ryue Nishizawa

Casa Mora, 2000-2003

Abalos y Herreros

Office 7, Summerhouse, 2004-2008

OFFICE KGDVS

Mies van der Rohe

Thesis House, 1942

Philip Johnson

Patio Villa, 1984-88

OMA, Rem Koolhaas

Weekend House, 1997

Ryue Nishizawa

Casa Mora, 2000-2003

Abalos y Herreros

Office 7, Summerhouse, 2004-2008

OFFICE KGDVS

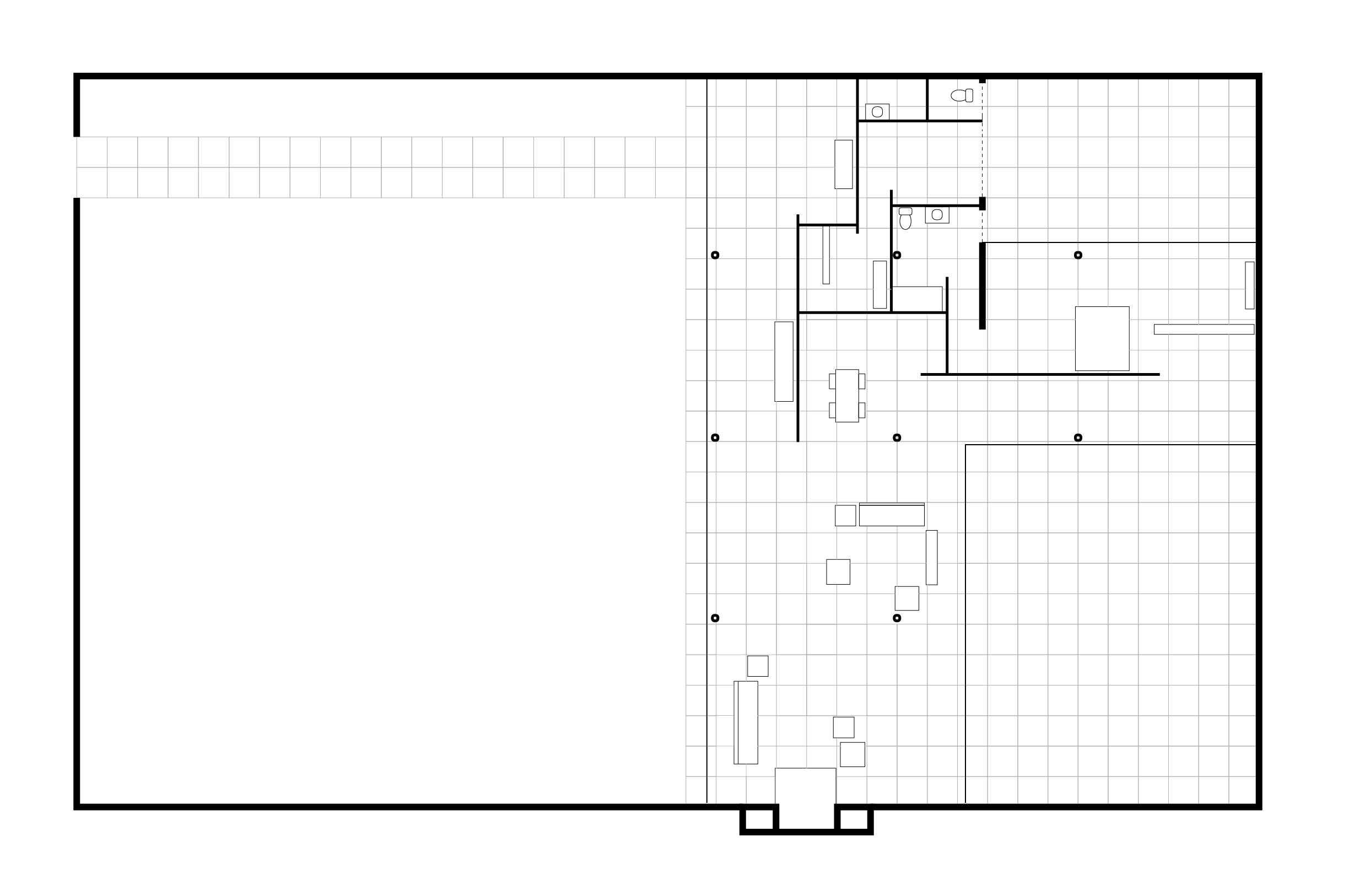

The court-house’s basic principles originate from Mies’ abstract lesson for young architectural students that he started at the Bauhaus and carried on to his pedagogy at IIT. A low-house with minimal elements to focus the execution of the brief. Philip Jonhson’s 1947 Moma catalog serves as the foundations for the naming and grouping of these enigmatic projects and he presents them as a decade-long ambition of Mies’. His own description of the project is most clear, “from 1931 to 1938 Mies developed a series of projects for ‘court houses’ in which the flow of space is confined within a single rectangle formed by the outside walls of court and house conjoined. The houses themselves are shaped variously as L's, T's or I's and their exterior walls, except those forming part of the outside rectangle, are all of glass.” Strangely enough, the court-house concept would not be a defining architectural motif in Mies work, but potentially reveals, as an assignment, a working definition of architecture.

In the architectural brief at the Bauhaus, students would draw hundreds of variations alongside their professor, embedding the tendencies and tone of the court-houses into his pupils. The real assignment of all this repetition was “to judge ‘what good architecture is.’” In defining the elements of the court-houses, Mies is actually defining his view of the medium of architecture: the high-walled rectangular district, free-standing partitions, a flat geometric roof, a glass enclosure, point-load columns, free-flowing circulation and the spartan use of furniture altogether creating a definition of the space largely legible in the plan. It is through these limited tools that one can see what architecture can do that other mediums cannot.

Mies van der Rohe

Court-House Study

1931-38

Court-House Study

1931-38

The fundamental nature of the court-house construction, its rectangular frame-like legibility and its displacement from its context make it an ideal project for “authoring” in the fuzzy medium of architecture. The definition of the house in a frame makes it particularly medium specific. In an essay by Iñaki Abalos on the court-house, House for Zarathustra, he argues that the court-house is an act of self-construction. Abalos focuses on the clarity by which Mies renders the subject within. An Übermensch, an urban man, a godless house, a place of reflection, wearing hand-stitched leather shoes, a man who needs to be close to the Agora. In the end, Abalos says that “Mies was creating a self-portrait, he was offering his own person as a project.” Reading the court-houses through this mind-set – we look forward to the “self-portraits” made by the architects who examine the problem for themselves, instilling their own distinct mark on the brief and the medium.

Philip Johnson

9 Ash St. House (Thesis House)

1943

Mies’ court-houses we’re never realized by himself, but there is a doppelganger in Philip Johnson’s 9 Ash St. house, otherwise known as Johnson’s “Thesis House.” He built the house for himself during his formal schooling at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, after he’d already been the successful architecture curator at MoMA. Johnson executes the court-house with Miesian clarity. Despite its brickless design, the house is incredibly inattentive to its neighbors, a protected precinct with a high wall, a planar glass enclosure dividing the precinct, point-load columns with chrome-plated connections and a flowing interior space with limited partitions.9 Ash St. House (Thesis House)

1943

In a 1943 issue of Architect Forum, the unknown author makes two statements 1– 9 Ash Street, it “is probably the best example” of Mies’ attitude towards architecture and 2– “Few people would be at ease in so disciplined a background for everyday living. But the architect, as we have seen, was not concerned with the requirements of anybody except himself.” Even in this contemporaneous account, the acknowledgment of the house’s hyper-specific approach should be considered a surprise considering its deeply abstract aura and considering how Mies’ and Johnson’s lifestyles and geographies might differ.

Rem Koolhaas (OMA)

Patio Villa

1984

The first of the contemporary reconstructions of this brief would be Rem Koolhaas’ Patio Villa (Dutch Section, House for Two Friends) in 1984-1988. At the height of postmodernity, Koolhaas was at the peak of his Miesian fantasies; Friedrichstrasse Housing in 1980 (which directly credits the court-houses in S,M,L,XL), Casa Palestra at the Milan Triennial in 1985-1986, the Video Bus Stop in 1991 and Nexus World Housing in 1991. This house will be OMA’s first project in S,M,L,XL on the page following the opening note titled “The House that Mies Made.”

Patio Villa also bears the same name as the European colloquial name for the court-house. The house’s location on an embankment creates the condition of an entrance on the lower level, but the garden on the upper level. These conditions allow Rem to undertake a few small experiments, but notably the translation of the Patio from the enclosing space to an object-void and the introduction of sectional openness through the house.

The house itself is an inversion of the basic Miesan principle, placing a patio as the subject inside the house rather than the definition of the exterior. The court actually becomes an object in the house as opposed to the frame. Rem calls the patio an “empty heart” of the house– in this way the space is a representational void that embodies the ecstatic hedonism of the modern movement that Rem often tries to recapture. The object-void actually penetrates the entire house, with the glass floor of the patio actually serving as a lightwell for the lower level gymnasium below. During this same time at the 1986 Milan Triennale OMA presents Casa Palestra where they present this type of hidden hedonism of Physical Culture through a transformation of the Barcelona pavilion into “somewhere in the ambiguous zone between exercise and sexual pleasure.”

In a 2008 interview, Rem claims that one of OMA’s primary contributions to architectural discourse is the translation of openness in plan, to section. The house is titled A Dutch Section in the monograph, referring to the house’s location on a dyke, but the house first experiments with this concept of openness in section. From the street entrance below, there is a direct uphill path from the parking area, through the house, up the stair alongside the patio to an outside boardwalk leading towards the woods. The path is reminiscent of the long paved pathway drawn in Mies’ House with Three Patios, this time moving through 3-dimensional space in a way we’ll see become a trademark of the practice later on. Koolhaas’ desire to achieve the court-house type along with the constraints of the site led to a redefinition of architecture, especially in section.

Ryue Nishizawa

Weekend House

1997

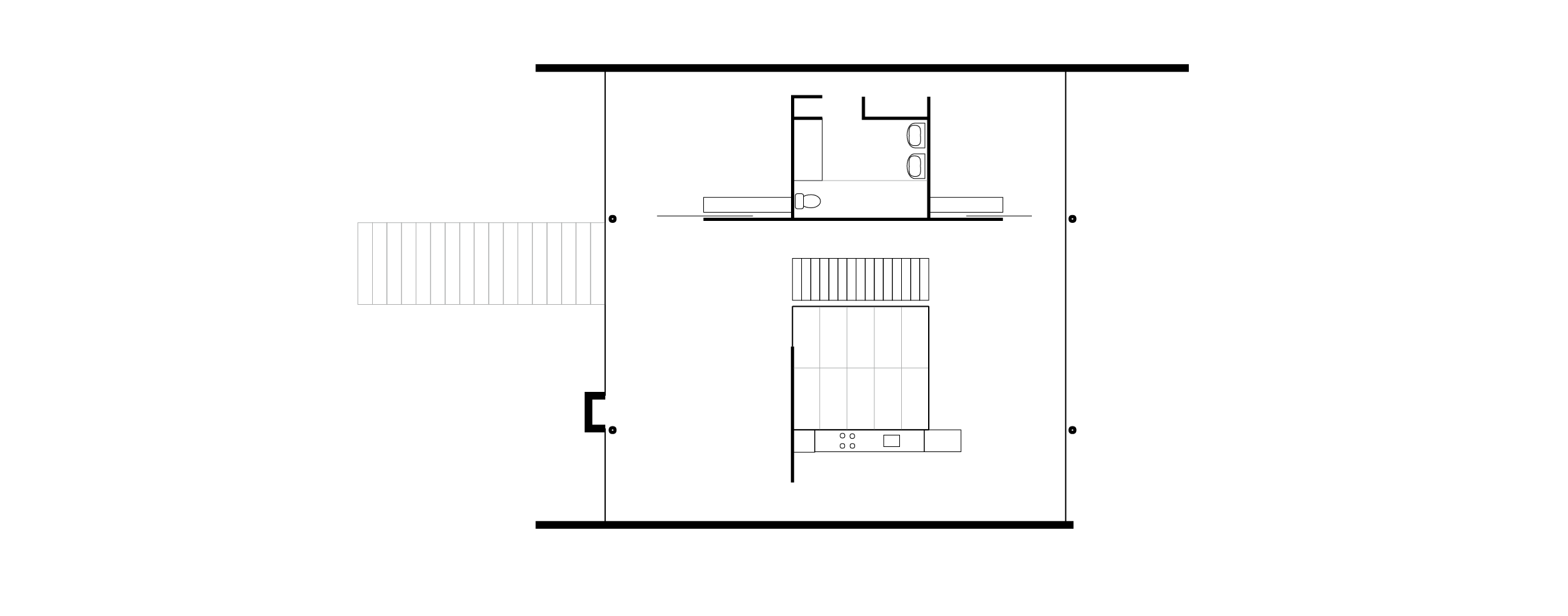

Ryue Nishizawa would also take on the court-house brief in his project Weekend House in 1997. A low crisp black volume, the house is a single story with three patios presented within the boundary. This house displays many Miesian tropes, an extruded column grid, a suppression of verticality, a low chimney, intense planarity between the floor and ceiling, and an incredible openness throughout making the project nearly partition-less.

While Nishizawa had been practicing with Kazuyo Sejima for over 10 years, the Weekend House is the first project in establishing the Office of Ryue Nishizawa, a separate office from the one he shared with Sejima. Like the Mies house, the design is incredibly internalized, creating a unique set of rules within the boundaries of the house that establish a universe with its own rules and sense of gravity. The main articulation of the plan is a dense grid of columns (2.4m square modules) and the introduction of courtyards as spaces of division rather than connection. Unlike Mies’ houses, the differente spaces of the house are separated by the courtyards rather than with partitions. In fact there are no freestanding interior partitions at all. The glass is transformed from being a transparent surface to an opaque one. These glass partitions establish an entirely different sense of continuity then the other houses.

The myth that glass is perpetually transparent is debunked by Nishizawa here, showing how in the correct use, glass can be a source of division and light. Nishizawa’s continual experiment with privacy and shared living depend on establishing the contradictions between openness and opacity. The house, legible as a house with three patios, eschews the need for interior partitions whatsoever from Mies’ original brief, but shows how the combination of a dense column grid and transparent partitions can be enough to establish the intimacy and articulation of the uses in the house.

Abalos Herrero

Casa Mora

2001-2003

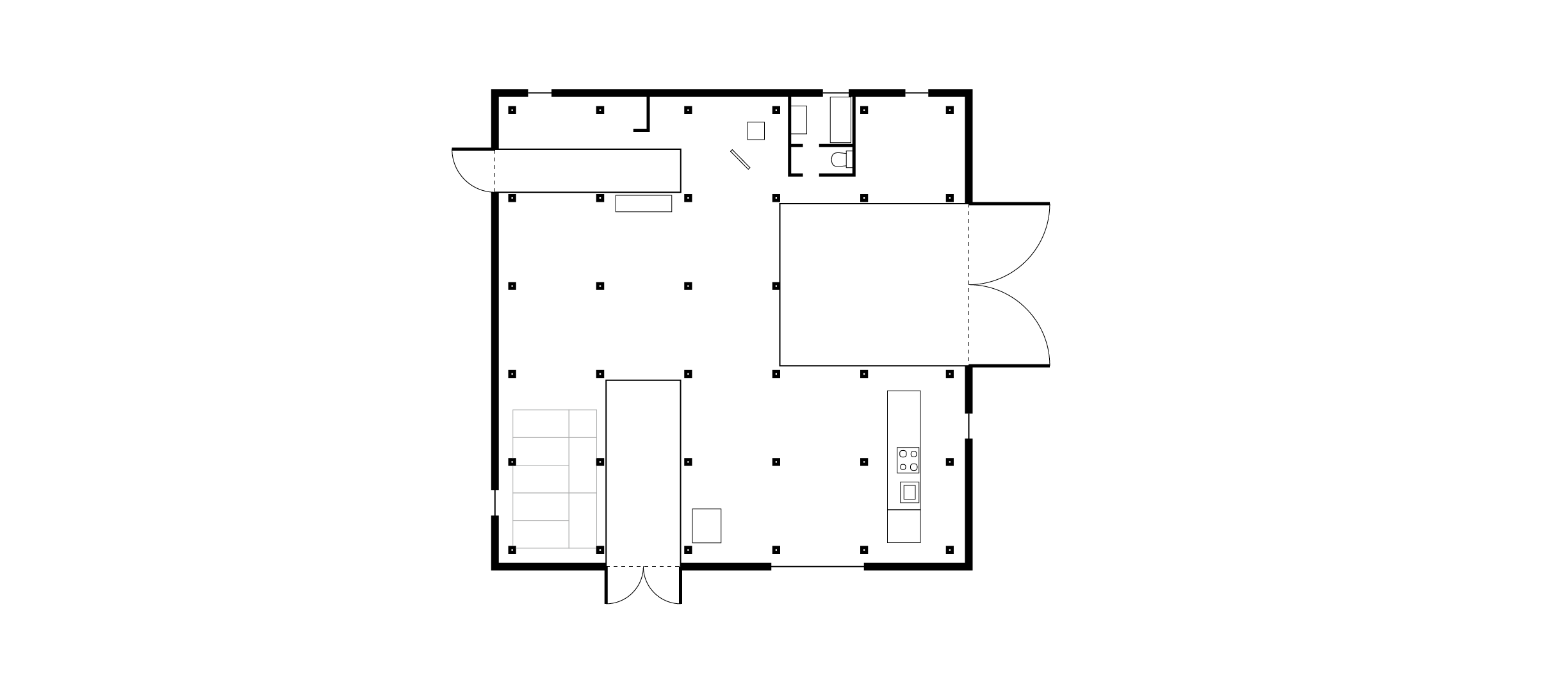

Iñaki Abalos and Juan Herreros design Casa Mora in 2001-2003– it is not their first house, but simultaneous to designing this project, Iñaki writes his essay on the subject of self-construction in Mies’ court-houses, published in 2001. Casa Mora remains unbuilt, but is presented in a series of plans with an almost identical proportion to Mies’ House with Three Courtyards. The house explicitly rejects Mies’ free plan, glass partitions and column grid, but preserves the flowing space and lack of hierarchy between parts by introducing a relentless grid of rooms. To articulate their closeness with Mies’, Abalos and Herreros show a nearly functioning furniture plan with all of the walls removed revealing their intentional closeness to the project. In Mies’ houses, the continuity of uniform space is one of the guiding principles (rarely are there discernable doors, rooms or passageway), but in Casa Mora we see how in a uniform blanketing of rooms, a deeply miesian aura emerges by reducing the hierarchy of highly specific parts.

In the case of Casa Mora the district wall is equal in hierarchy to the interior walls with no differentiation in even wall-type. The entire house is built with thin walls that are indiscernible from even the glass ones. Using the five linear divisions of rooms the “court” is distributed amongst the variations. The innovative approach here is to articulate a clear frame around each domestic part (living room, kitchen bedroom) therefore eliminating the need for any relationships between the parts. Much of the compositional effort in the original court-houses would have been organizing the domestic parts in a way that satisfies the functional needs in contradiction to the openness of the plan. Casa Mora’s strategy eliminates any need for direct or opposed relationships by saturating the district with frame-like partitions, each enclosing specific domestic functions. Abalos and Herreros also present a series of variations of the plan, articulating that there is an indifference to the organization of these rooms presented in their fixed state. While the rooms themselves are highly specific, the dense grid allows for their specificity to be indiscernible to the whole – an undeniable evenness is the texture of the plan and it embodies a similar continuity of space of the court-houses.

This approach is essentially an introduction of domestic frames that each capture a specific function, but this concept does not attempt to accentuate the differences between the domestic programs, but instead allows the distinct variations to be low-impact towards the overall design. The introduction of specific spaces not only proves that the approach is successful, but further expands the possibilities of the court-house as an act of self-construction. Swimming pools, parking garages, libraries and offices populate the plan without any disruption to the overall logic or attitude. The entire space, with its flexible grid of domestic parts, is made from an endless and rhizomatic set of programs, indifferent to their organization within the whole.

Office KGDVS

Summer House

2004-2007

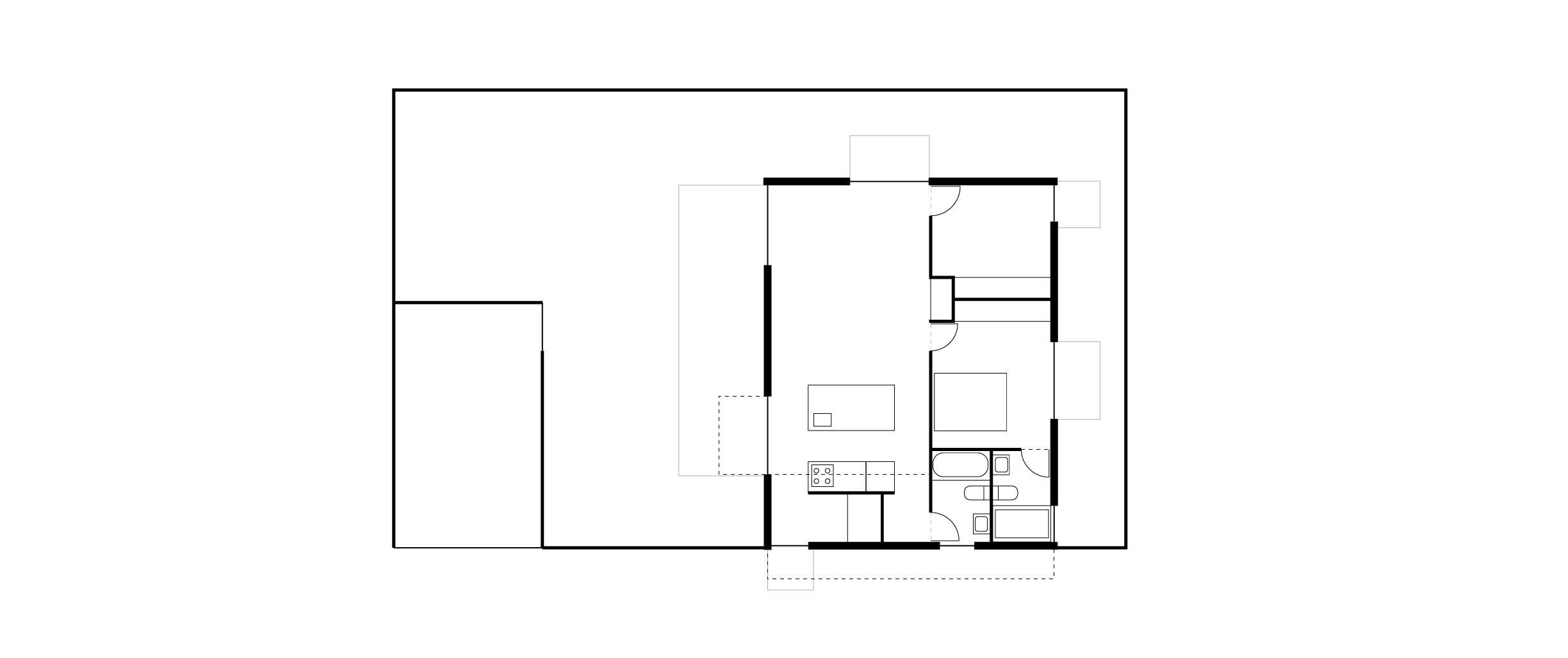

OFFICE KGDVS extends an existing house which they call a Summer House, but knowingly refer to it as a ‘patio villa.’ It is their first house design which they widely publish (designed built in 2004-2008) and it marks a distinct switch from other previous approaches by the reintroduction of a more literal take on Mies’ court-house, but by redefining the boundary wall material and siting, establish a new approach to the court-house project.

The extension has very miesian articulation – a roof resting on a rectangular wall forming a large patio, a continuous set of square concrete pavers, and a glass partition dividing conditioned space from unconditioned. Pulled out of its context, The Summer House is clearly legible as a court-house variation with the notable district and glass partition, but within its context, the house activates the leftover space between the district boundary and the irregular lot. The porous district boundary wall created with 290cm high steel posts, allows for absolute clarity of the precinct, but the space between itself and the irregular lot shape is put to use with functions like wood storage, an outdoor kitchen and a laundry room. The district no longer becomes the space of specific use, but instead an empty space allowing for an abstract life to unfold within. In OFFICE’s case, the advantage of the court-house is creating the legibility of nothingness to an existing space. By evacuating all usefulness from its interior, (other than square-footage itself) OFFICE reinterprets the court-houses not as a house at all, but a resistance of typology in-lieu of a pure geometric clarity. The geometricized emptiness of the district becomes the defining logic of this project and their project beyond.

All of these reconstructions engage with the same architectural parts as Mies’ originally presented– the walled district, the glass partitions, the point-load columns, and the free-flowing space. Each time the court-house is reconstructed, new concepts and theories are overlaid on top of Mies’ original project. The question remains, why are these architects immediately drawn to the project to start? The simplest reason may be that the clarity of the project presents the most succinct opportunity to be both architecturally conversive and fulfill the enigmatic briefs of various clients.

NILE

The Other House2017-2019

In 2017 (before identifying this phenomenon) I found myself in a curious position. In the middle of designing my first house, holding all the anxiety of the inaugural project, I have a narrow obsession trying to realize aspects of Mies’s House with Three Patios. I couldn't shake the feeling and deep desire to realize a variation of the court-house. I hadn’t put together this lineage and I was not intending to contribute my own variation to the brief, but nevertheless I was non-stop thinking about how best to reconstruct the house for this specific client. Under this psychic energy, I contributed my own project, The Other House as my inaugural house project.

By 2019, The Other House is complete and I’ve put together the chronology of court-houses reconstructions. Our project is defined by an oversized roof sitting on top of a continuous garden wall, overhanging on the entrance side. A 6’-8” fence forms the district around it with the interior and exterior walls inscribed with a 6’8” dividing line. An oversized 4’-6” high roof appears to sit on top of that district boundary. The enclosure of the house is defined by simple walls that sit below the line demarcating the roof from the walls. The gaps between the walls are filled with 6’-8” sliding glass doors (no windows). The house’s walls are always linear with open ends, never forming a corner between them. Any corner of the interior or exterior is articulated with a door or circulation. Through each glass door, a patio is partially articulated, continuing the space from inside to outside and vica-versa. The interior space is defined through a similar horizontal datum that rests directly on the height above the windows and doors. The oversized roof hangs off of the entry-side, forming an overhang at the entrance.

The planarity, articulation of the elements and discipline in this project remains closely associated with the court-houses, but in this case, the singular glass wall is replaced with an articulation of the interior partition language for the enclosure as well as. In this approach, the interior and exterior of the house, maintains the same logic of free-flowing spaces around partitions rather than having this glass dividing line from one to the other. This interpretation allows the entire district to transform into the language of the interiors, eliminating the hierarchy of the continuous glass partitions as the dominant language of enclosure, instead the door (once again historically) becomes that language. There is a prevalence in American houses to create an architectural object raised on a pedestal with small extensions of the interior, in the form of balconies and patios. These outdoors areas are often expressed as a part of the architectural object with handrails and eaves to match (think prairie-style houses). In our case, the language of the interior takes over the entire site, continuing the logic of free-flowing space and horizontality across the district and eliminating the hierarchy between the architectural object and the exteriors. By eliminating a strong hierarchy between the house-object and it’s private boundary the entire district becomes a continuous architectural gesture moving horizontally across the entire planar surface of the district. The reduction of hierarchy and the preservation of the horizontal are primary elements that make up our design philosophy, and realizing this house has informed much of our current thinking.

Now, let us draw a distinction between Mies’ court-houses and the Court-House Project. Each of these examples represents a contemporary reconstruction of the unbuilt modernist icon, and these reconstructions are what defines the Court-House Project. I’d like to make the case that the Project can be presented as a solid contender for what defines the medium of archtiecture for Mies van der Rohe and the project’s primary conditions establish a perfect frame for the execution of architecture specific concepts by other architects. Mies clearly did not intend for these early studies and student projects to become an act of self-generation for architects today. Just as the court-house’s we’re miscredited to just Mies when many of them are in fact student projects, the Court-House Project also no longer belongs to Mies. The Project no longer offers Mies as the solitary subject, but instead serves as a medium for describing architecture as a discipline.

This piece was adapted from an August 2018 piece by Nile Greenberg for Cartha Magazine on “Building Identity.”

2G nr. 22, 2002: Abalos & Herreros. 2002. GG. Riley, Terence, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Barry Bergdoll, and Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani. 2002.

Mies in Berlin. New York: Museum of Modern Art. Mertins, Detlef. 2014.

Mies. Phaidon Press. Mertins, Detlef. 2011. Modernity unbound: other histories of architectural modernity. London: Architectural Association.

Abalos, Iñaki, Paul Hammond, and Iñaki Abalos. 2017.The good life: a guided visit to the houses of modernity. Houses, Unknown Author, The Architectural Forum, December 1943. Pg. 91 Heidingsfelder,

Markus, Min Tesch, and Rem Koolhaas. 2012. Tem Koolhaas: a kind of architect. Berlin: absolut Medien.

Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.), and Philip Johnson. 1978. Mies van der Rohe. New York: Museum of Modern Art.

Geers, Kersten, David Van Severen, and Bas Princen. 2017. OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen. Volume 1.